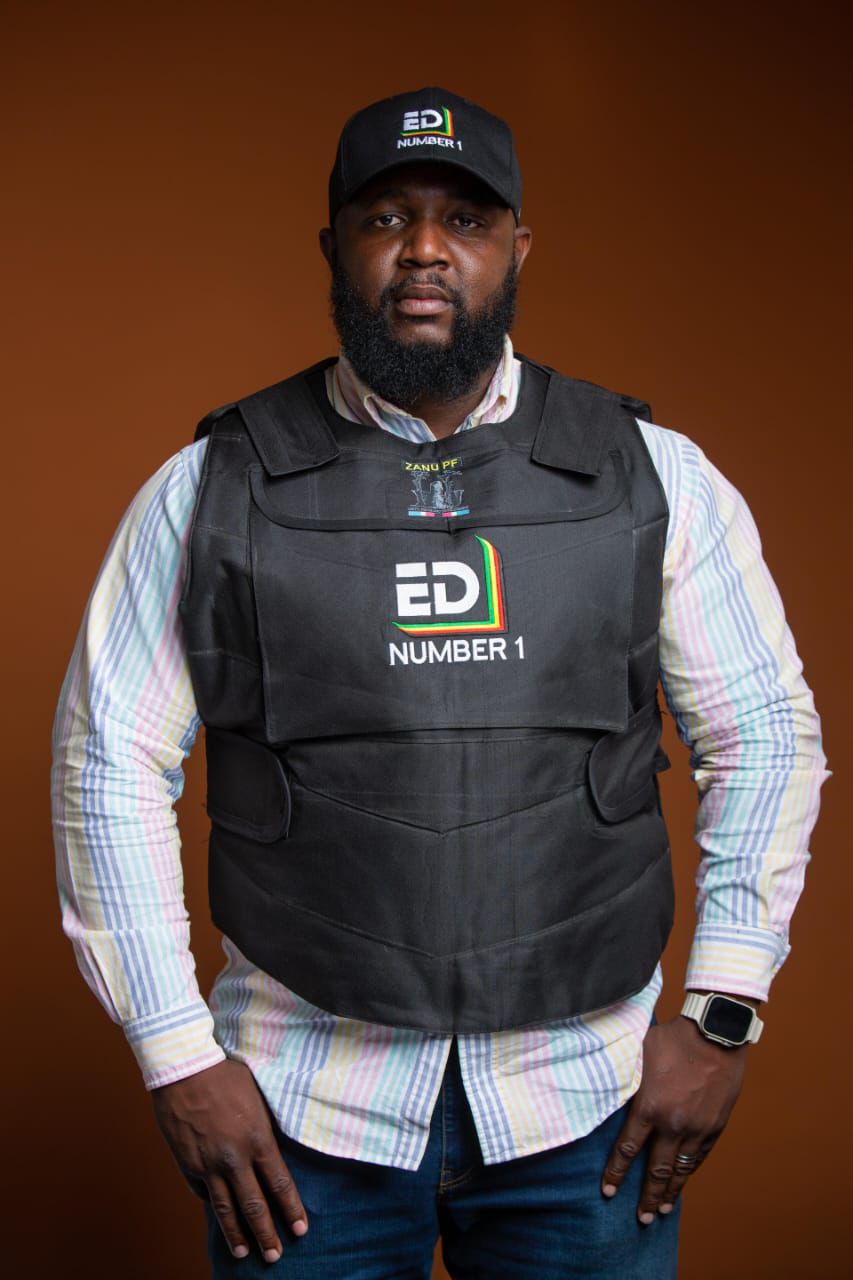

In an exclusive interview, Dru Edmund Kucherera, the National Vice Chairman and Spokesperson for Miners for Economic Development, has moved to correct the public record regarding Zimbabwe's Indigenisation and Economic Empowerment legislation. He asserts that the recent Statutory Instrument 215 of 2025 does not represent a reintroduction of a scrapped law, but is rather the latest evolution of a policy that has been in continuous effect since 2008.

“It is wrong to assume that the Act for indigenisation was abolished or scrapped in totality and that it is being reintroduced,” stated Kucherera. “The particular law, in fact, has evolved significantly from its initial hardline position.”

A Policy in Flux: From Blanket Rule to Targeted Reservations

Providing a detailed history for context, Kucherera explained that the original 2008 Act mandated a blanket 51% ownership cession by non-indigenous businesses, defining “indigenous” as those historically disadvantaged before 1980 to address economic imbalances.

“The Act was introduced in 2008,” he noted. “The key shift began with the Finance Act (No. 1) of 2018, which amended the 2008 Act. It moved the policy from a blanket 51% equity transfer to a system of targeted, sector-specific reservations.”

This evolution continued, he said, with the Finance Act (No.2) of 2020 repealing the 51% requirement even for the diamond and platinum sectors, leaving only the framework for reserved sectors to be defined by ministerial regulation.

“It therefore follows that S.I. 215 of 2025 is the culmination of those provisions for reserved sectors,” Kucherera concluded. “It is not a new law, but the detailed implementation of an existing policy framework.”

Unpacking S.I. 215 of 2025: Divestment, Declarations, and Sanctions

The new regulations, according to Kucherera, are built on two pillars: limiting foreign participation in certain sectors and enforcing transparency.

The instrument mandates that existing foreign businesses in exclusively reserved sectors must divest 75% of their equity over three years, with a minimum of 25% per annum. To prevent circumvention, the regulations require sworn affidavits declaring beneficial ownership and prescribe criminal and civil sanctions for violations.

The Reserved Sectors: Protecting Local Enterprise

Kucherera outlined the sectors now exclusively reserved for Zimbabwean citizens, which include passenger transport, barbershops, bakeries, artisanal mining, tobacco grading and packaging, pharmaceutical retailing, and the marketing of local arts and crafts.

“The rationale,” he explained, “is that these reserved areas do not require high capital to start and are a serious opportunity for local citizen employment and enterprise.”

Conditional Access: High Investment or High Employment

For conditionally accessible sectors, foreign investors face a high bar. They must apply for “Qualified Foreign National” status by demonstrating significant value addition.

For example, to participate in retail and wholesale trade, a foreign entity must employ a minimum of 200 people or invest at least US$20 million. Grain milling requires either 50 employees or a US$25 million investment.

“The foreign investor will have to submit business plans which prove, among other things, significant employment, technology, and skills transfer,” Kucherera stated.

In summary, Kucherera’s analysis positions S.I. 215 not as a sudden policy reversal, but as the next logical step in a long-evolving indigenisation strategy—one that has moved from broad-based ownership transfers to a more nuanced model of sectoral protection and conditioned foreign investment.